Unlocking the Secrets: How to Craft a Compelling Research Question

Identifying a Knowledge Gap in your research is one of the most common questions from researchers, especially younger colleagues getting started ... (Bumper post with new webinar invites ....)

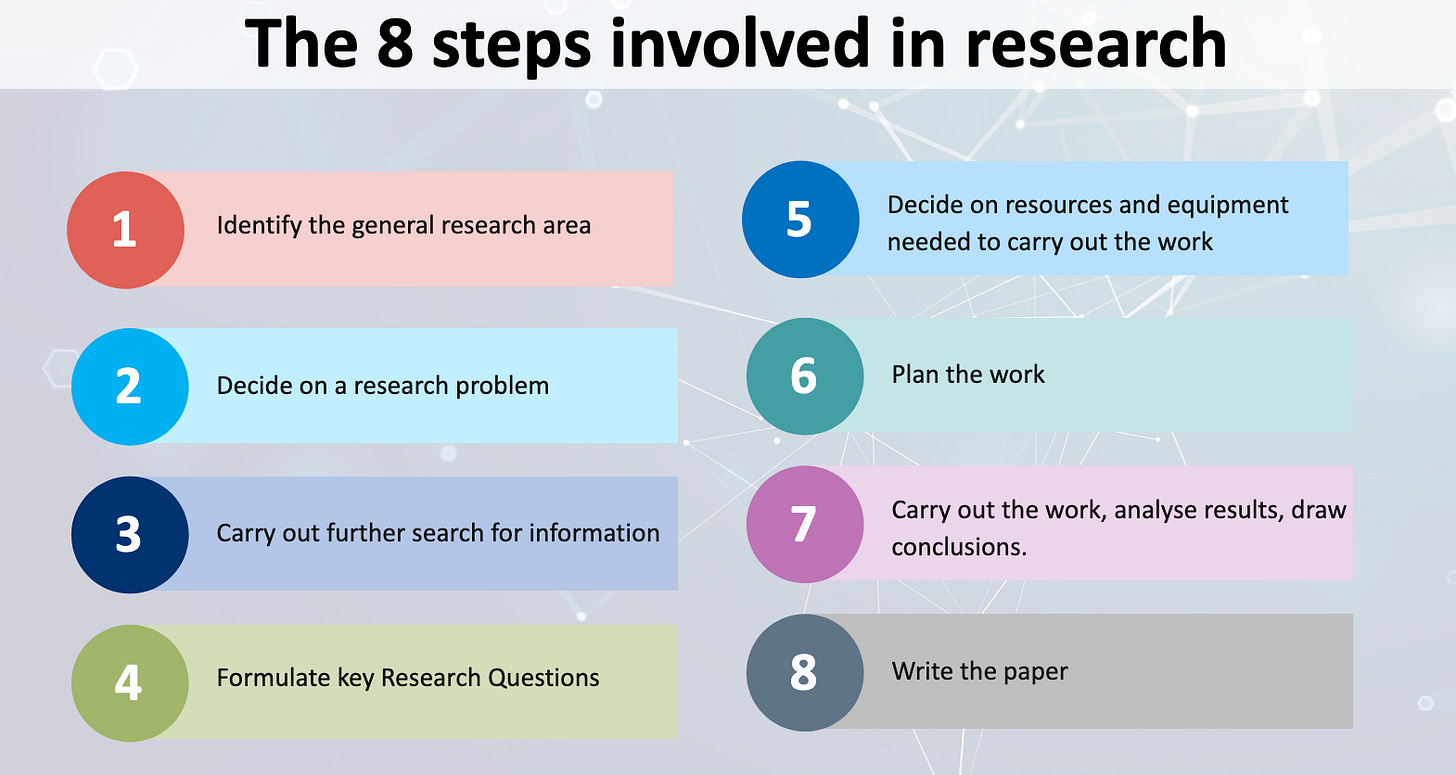

Research is the cornerstone of progress in any field. Whether you're a student embarking on an academic journey or a seasoned scholar aiming to push the boundaries of knowledge, the first and most crucial step is formulating a compelling research question, also known as a Knowledge Gap.

A well-crafted question not only defines the scope of your study but also guides your research process, making it essential to get it right from the start. Here's a comprehensive guide on how to develop a good research question that can pave the way for a successful research endeavor.

1. Identify Your Passion

The most engaging research questions often stem from personal interest. Reflect on what truly fascinates you within your field of study. What questions keep you awake at night? Your passion will drive your research and keep you motivated during the challenging phases of your study.

Where do good ideas for research projects come from? This is a very common question: “How can I come up with good research idea?”. The answer is: give yourself time to think. Get away from the daily emails/meetings/university work. Here you have Bill Hamilton, a leading evolutionary biologist, who used to go fishing to come up with ideas. One of my favorite magicians (a hobby of mine) who always “sleeps with a pen and paper by his bed” in case he misses an idea. My ideas come from fossils: What’s your favorite dinosaur?

This section is sponsored by Virtus Publishing: You can get 20% off self-publishing your book with Virtus ….

In a series of posts within posts, our friends at Virtus Publishing will provide tips and advice covering many aspects of publishing. The first installment is a copyediting overview in four parts.

Copyediting Overview—Part 3: Querying

For a copy editor, confusing text can be like hitting a red light on the road. There are ways of resolving it (or even avoiding it completely).

No one says copyediting is easy, except those who have never done it. Along the way, copy editors will encounter text that may be confusing, contradictory with other parts of the text, or just unclear.

Querying is one way of resolving such issues but must be approached judiciously. The reality is that very often those who review a manuscript are too busy to thoroughly read what’s there. So queries must be short, concise, and clear. Queries must point directly to the issue being questioned.

By definition, in the copyediting realm querying is the process whereby the copy editor asks the reviewer about some aspect of a manuscript that may be incorrect or incomplete. It can be a difficult area for a novice copy editor to grasp or for even an experienced copy editor to master.

Some publishers may provide a list of acceptable formats for queries and might dictate exactly how and when queries should be used. Be careful when using these: “One size fits all” doesn’t always apply.

What is most important for the copy editor to realize is that in most cases authors will not recognize or even understand their errors or omissions unless they are pointed out.

Here’s what the CMOS says about querying. [The end of the quoted material is marked with a box [∎].

From The Chicago Manual of Style, section 2.66:

Editors may generally impose a consistent style and correct errors without further comment—assuming these changes are apparent on the edited manuscript. Corrections to less obvious problems may warrant a comment. Comments should be concise, and they should avoid sounding casual, pedantic, condescending, or indignant; often, a simple “OK?” is enough. Comments that are not answerable by a yes or a no may be more specific: “Do you mean X or Y?” Examples of instances in which an editor might comment or query include the following:

To note, on an electronic manuscript, that a particular global change has been corrected silently after the first instance

To point out a discrepancy, as between two spellings in a name, or between a source cited differently in the notes than in the bibliography

To point out an apparent omission, such as a missing quotation mark or a missing source citation

To point out a possible error in a quotation

To point out repetition (e.g., “Repetition intentional?” or “Rephrased to avoid repetition; OK?”)

To ask for verification, as of a name or term whose spelling cannot be easily verified

To ask for clarification where the text is ambiguous or garbled

To point to the sources an editor has consulted in correcting errors of fact ∎

There are two points in CMOS’s description worth commenting on.

1) I’d only use the simple “OK?” approach if the query is placed where the reviewer will see exactly what was changed. I avoid this approach and prefer to include what was changed in the query:

Author: “Blue” instead of “green” OK as changed?

2) CMOS mentions pointing out an error in a quotation: Be careful with this. What someone has said should never be changed, including errors in grammar. The purpose of including a quote is to be accurate. If the author says

We ain’t got no money. We’re doing our best.

It should stand. That’s why “sic” is often used. “Sic” is Latin for “thus it had been written,” which means that the quote was transcribed exactly as it was said, including any errors. “Sic” is usually shown in square brackets, like this:

We ain’t got no money [sic]. We’re doing our best.

It would be a mistake to change it to read

We don’t have any money. We’re doing our best.

Querying is the major difference between copyediting Levels 1 and 2. In Level 1, the assumption is that the text is reasonably well written and that the copy editor is unlikely to encounter significant issues. In Level 2, especially with manuscripts authored by non-native speakers, language issues are common. Querying in Level 2 is usually the limit in terms of what a copy editor should be required to do to address an issue.

In Level 3, querying often accompanies significant changes that are made: Because we have no way of knowing how attentive the reviewer will be, it’s critical to clearly point out significant changes or potential errors.

The biggest querying mistake I see on a regular basis is when the copy editor will say

Author: Please check sentence.

This rarely serves any purpose unless the copy editor points out exactly what is being questioned.

Making significant changes and querying in Level 3 is usually the limit in terms of what a copy editor should be required to do to address an issue.

Significant changes beyond rewriting fall under the category of developmental editing. We’ll discuss DE and other types of editing in Part 4 of this series.

When you’re copyediting, if you’re careful, consistent, and judicious regarding how and what you query, you can in most cases turn those reds lights to green and be on your way.

Stayed tuned for Part 4, when we’ll explore other types of editing.

Like this ‘post within a post’? Follow Virtus Publishing on LinkedIn!

Have you ever wanted to publish a book? Virtus Publishing’s self-publishing services can make it happen! A global service provider, Virtus has the industry experience and dedicated staff to turn your book idea into reality.

Send an email to david@virtuspublishing.com to set up a free consultation. Mention the keyword “Query” and receive 20% off your first order …

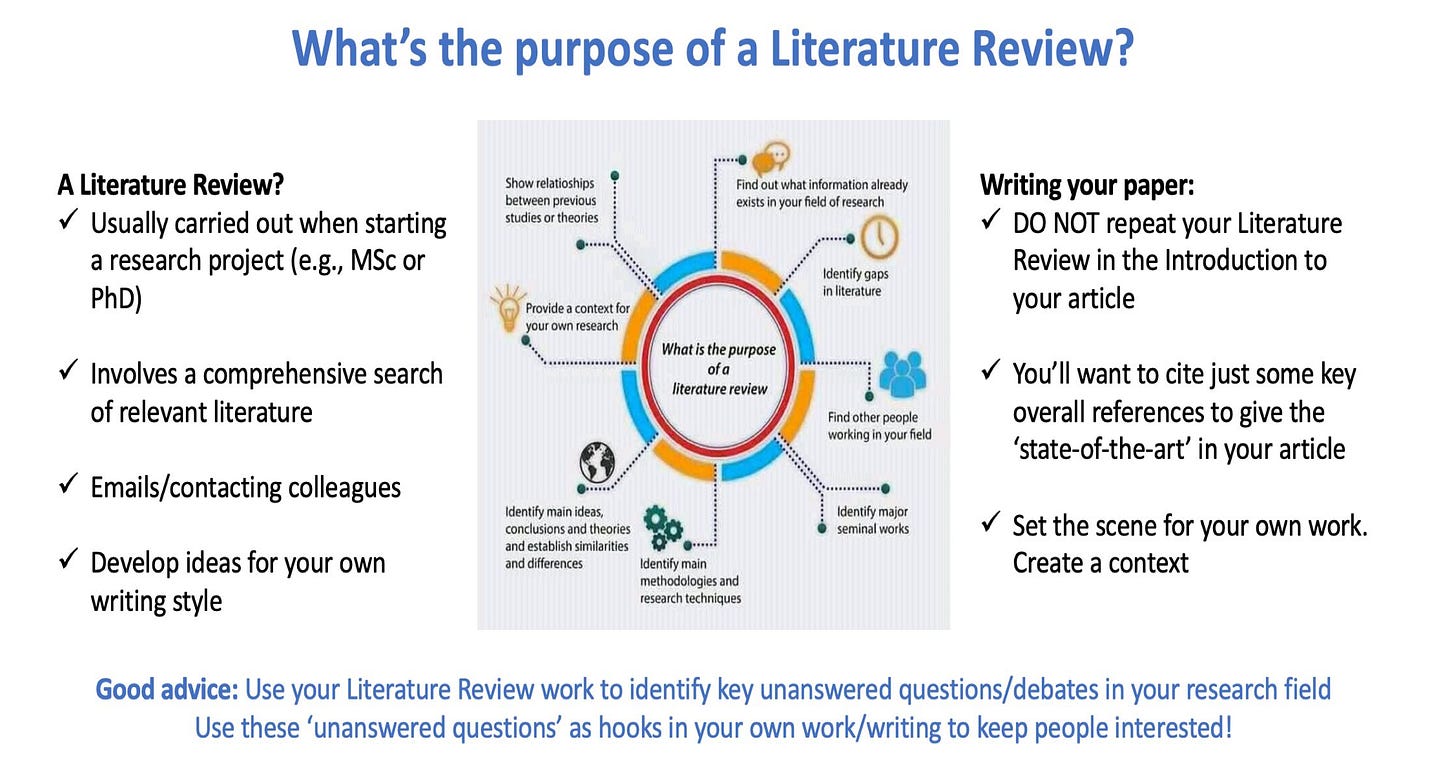

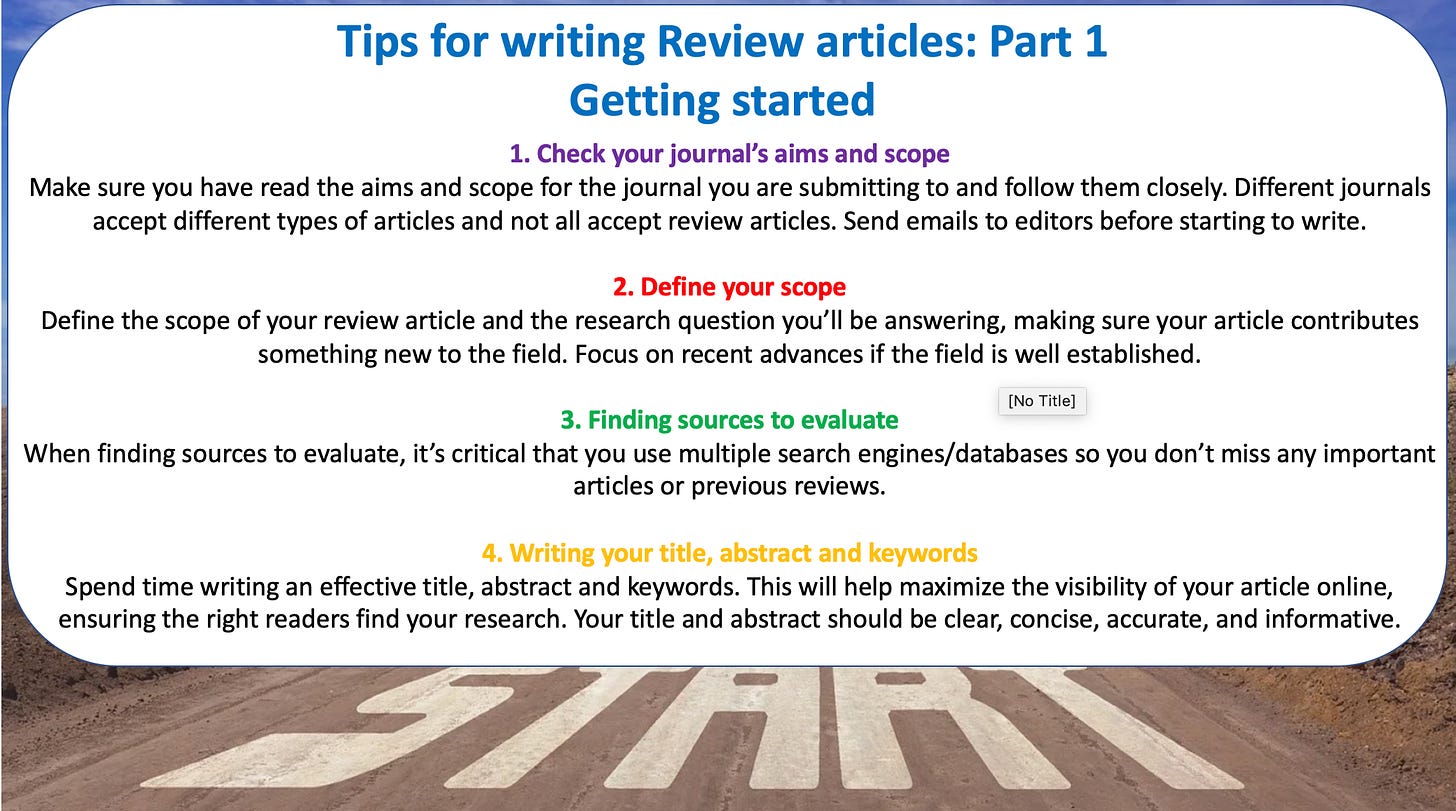

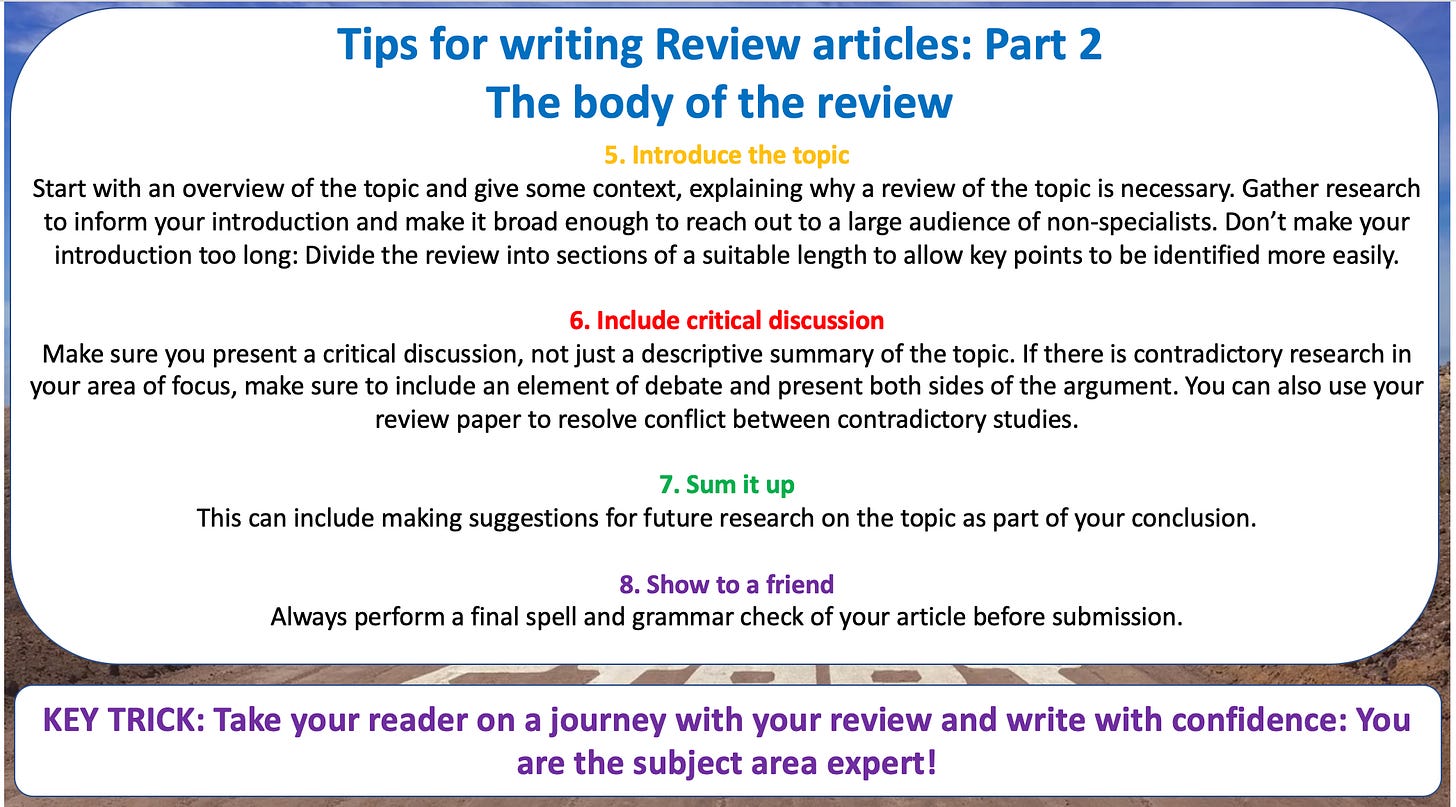

2. Explore Existing Literature

Conduct a thorough literature review to understand the current landscape of your chosen topic. Identify gaps, controversies, or unresolved issues in existing research. Your research question should aim to address or contribute to filling these gaps.

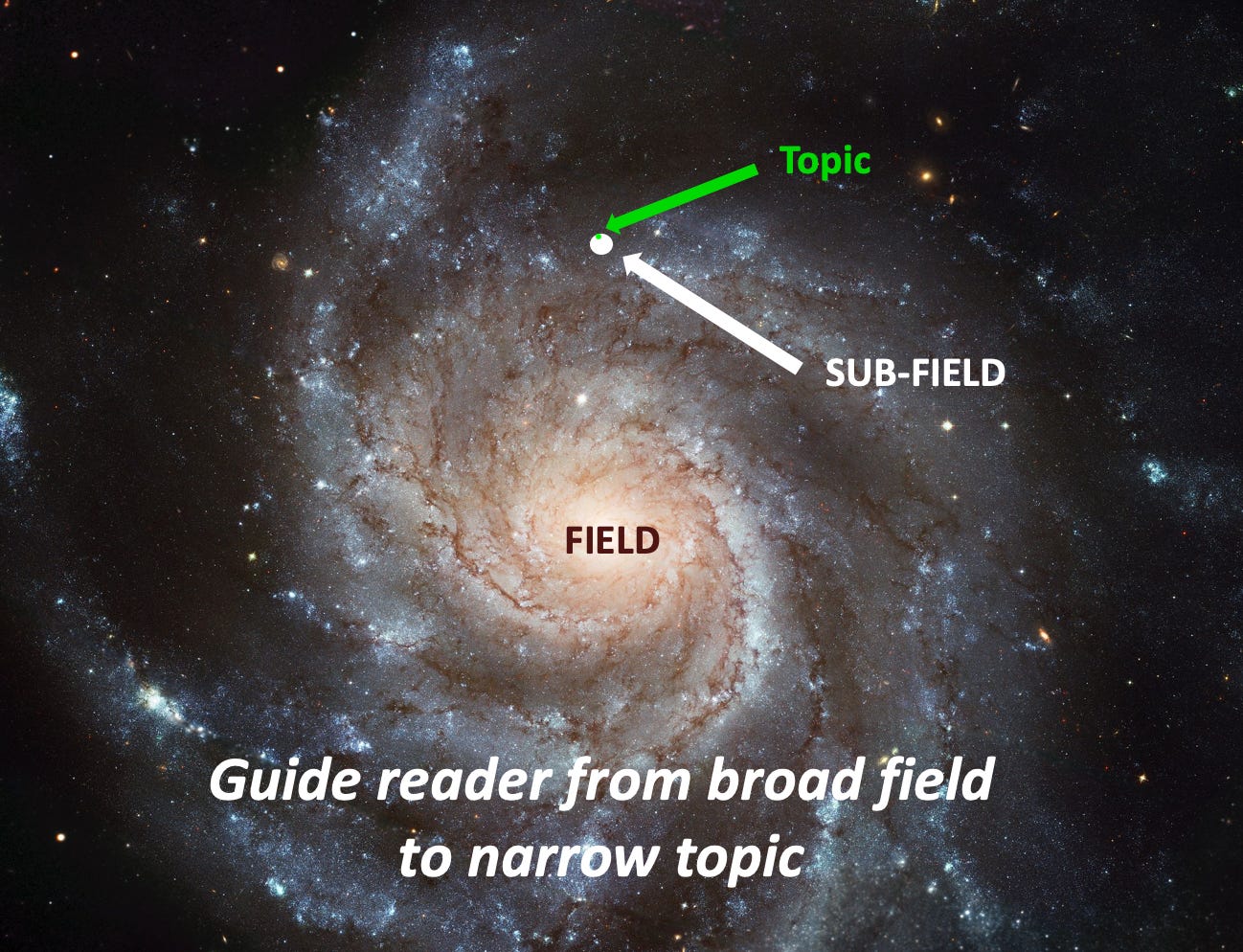

3. Narrow Down Your Focus

It's essential to narrow down your broad area of interest to a specific, manageable research topic. Avoid questions that are too broad or vague. Instead, focus on a particular aspect or phenomenon within your field. For example, if you're interested in climate change, you might narrow it down to a specific region's impact or a particular aspect of environmental policy.

4. Consider Feasibility

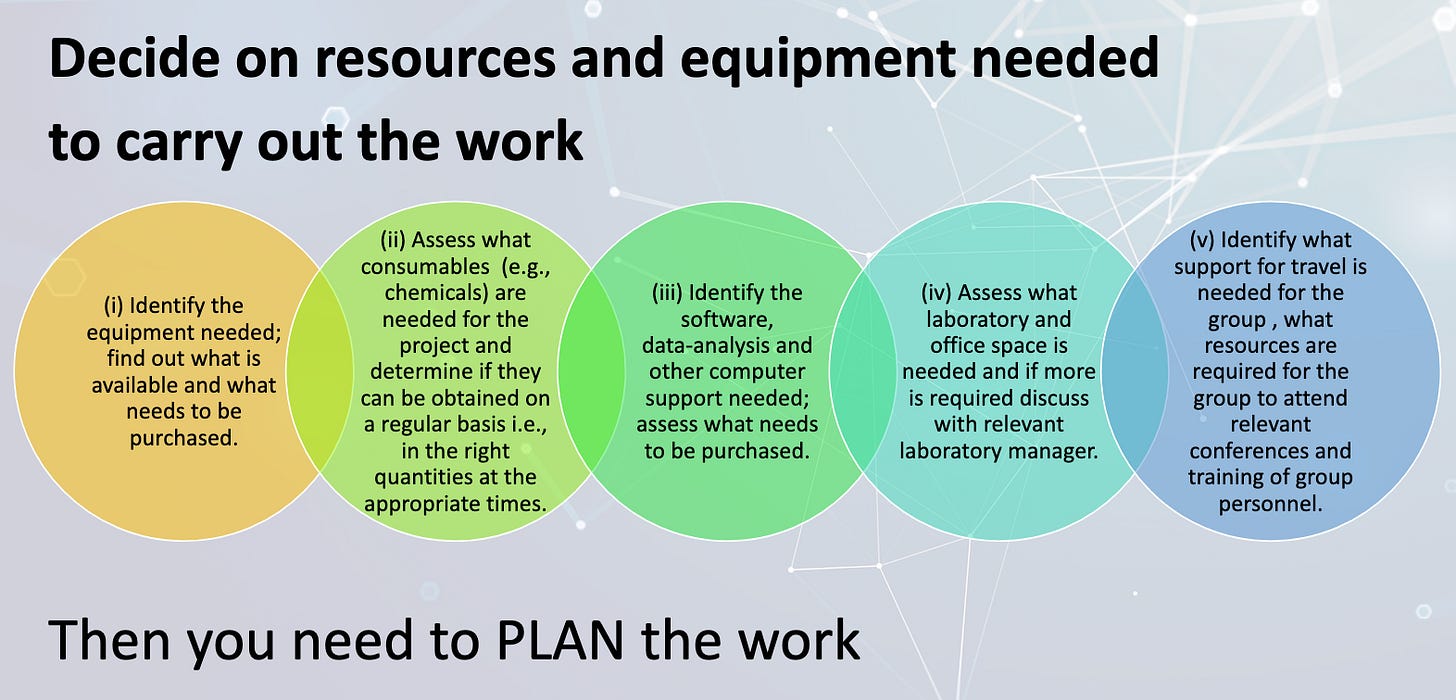

Evaluate the resources, time, and expertise required to answer your research question. Ensure your question is realistic and can be addressed within the constraints of your project. Avoid questions that are too ambitious or require resources beyond your reach.

5. Make It Clear and Concise

A good research question is clear, concise, and specific. It should be formulated in a way that is easy to understand and answer. Avoid jargon and complex language. A well-articulated question will guide your research and help you stay focused on your objectives.

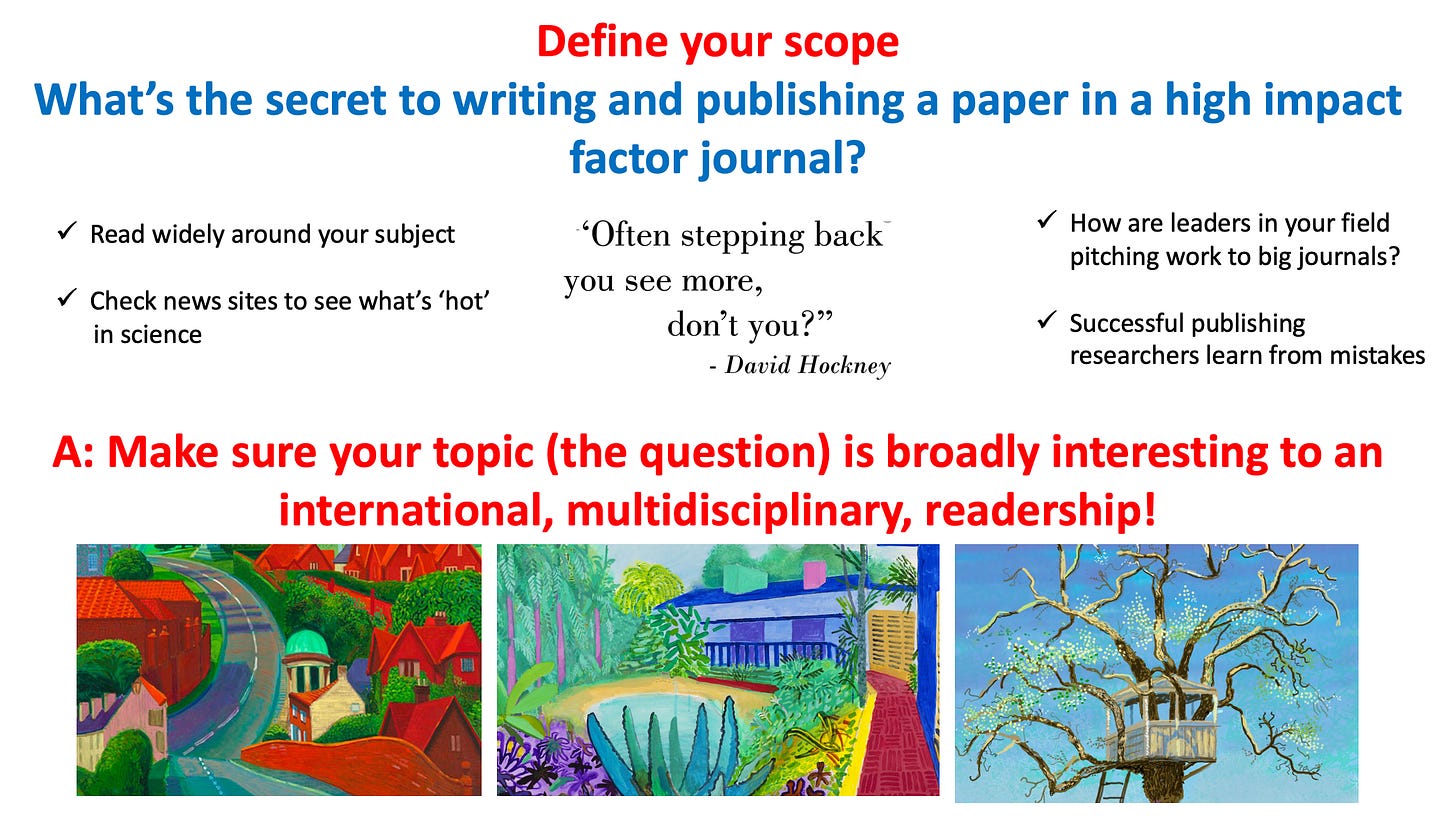

6. Ensure Relevance

Consider the significance of your research question. Will it contribute valuable insights to your field or address a pressing issue? A relevant question is more likely to capture the interest of your audience and fellow researchers.

7. Test Your Question

Discuss your research question with peers, mentors, or experts in your field. Their feedback can provide valuable insights and help you refine your question further. Be open to criticism and willing to revise your question based on constructive feedback.

8. Consider the Research Design

Think about the methodology you'll use to answer your research question. Certain questions are better suited for qualitative research methods, while others might require quantitative analysis. Ensure your question aligns with the chosen research design.

9. Stay Flexible

While it's crucial to have a well-defined research question, be open to adapting it as your research progresses. As you gather data and delve deeper into your topic, you may need to refine or modify your question to align with your findings and insights.

10. Seek Inspiration from Others

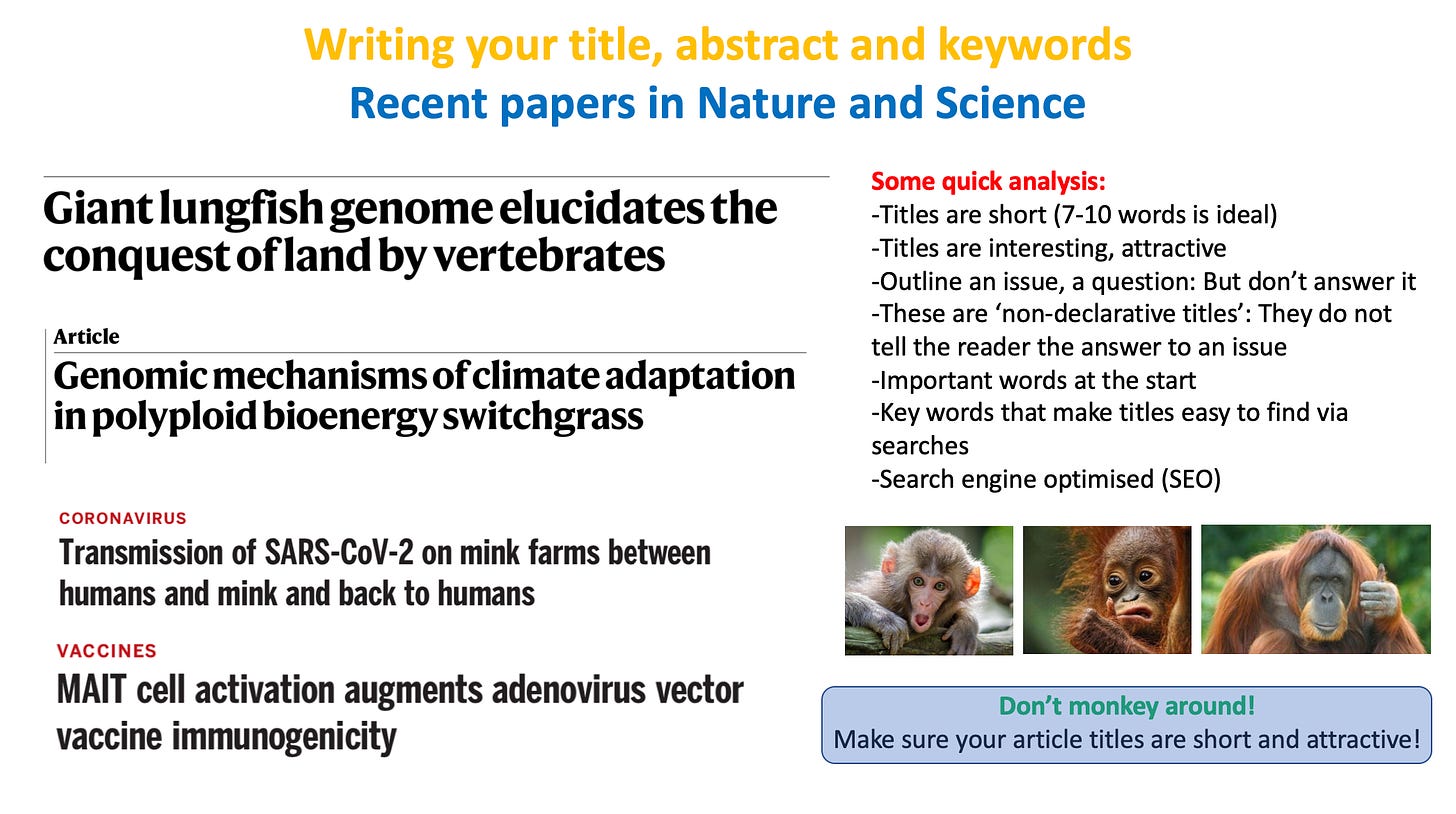

Read published research papers and articles within your field. Analyze how other researchers have formulated their questions and what makes them impactful. Drawing inspiration from successful examples can help you refine your own question.

Crafting a compelling research question is both an art and a science. It requires a deep understanding of your field, critical thinking, and creativity. Remember that a good research question is not just a statement; it's a roadmap for your entire research journey. By following these steps and investing time and effort into honing your question, you'll set the stage for a meaningful and impactful research study. So, dive into the world of curiosity armed with a well-crafted question, and you'll be on your way to uncovering new knowledge and making a difference in your field.