Understanding (and avoiding) the pitfalls of plagiarism in academic articles ... A quick guide ...

... and understanding the use of “Who” versus “Whom” .... Enjoy!

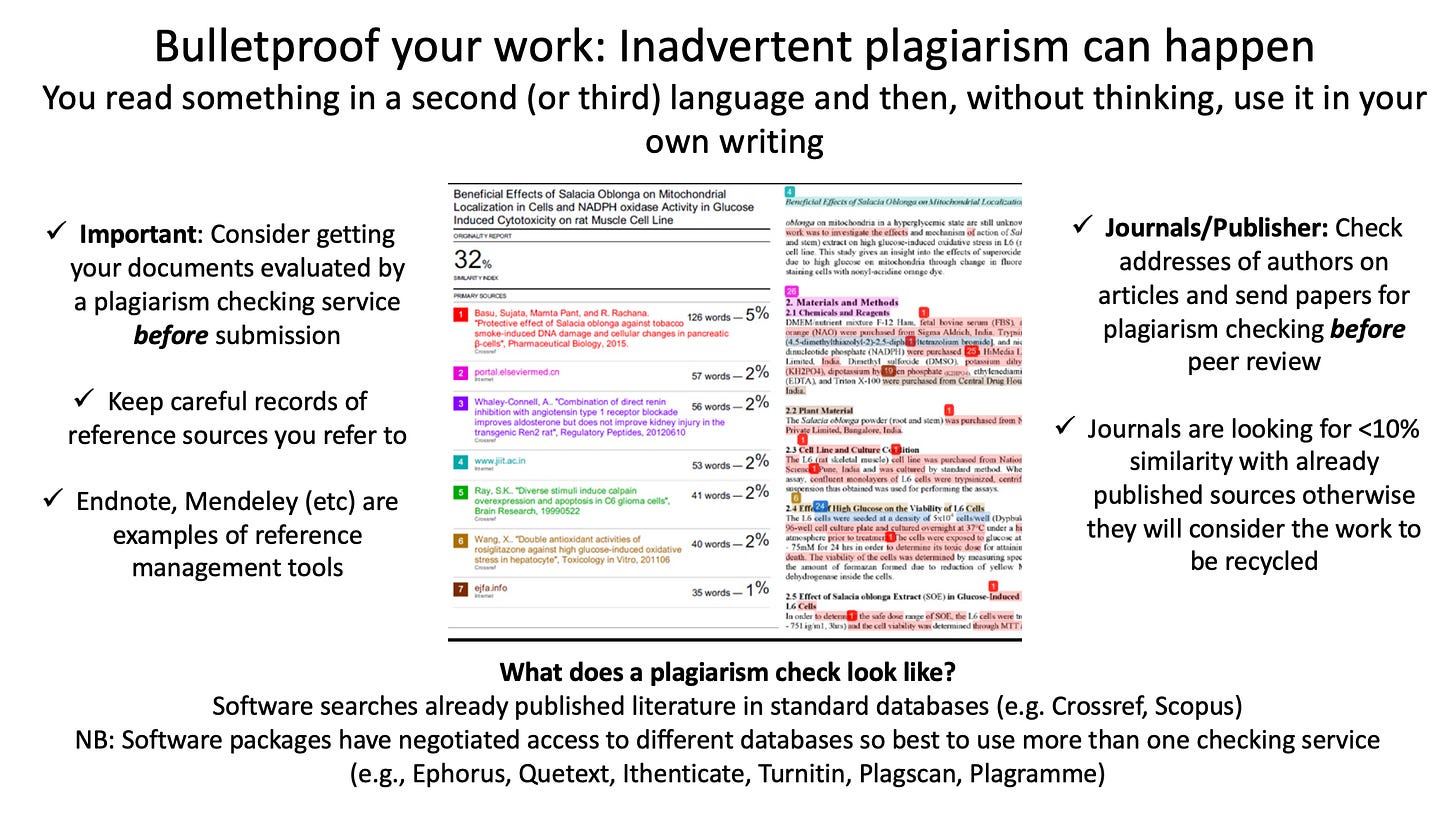

Data we’ve collected from major publishing companies reveal that one of the major reasons why papers received from ’English as a second language (ESL)’ authors tend to get rejected is because of plagiarism. This is because, very often, authors don’t realize they are using text from other papers without correct attribution; you know yourself, you read something in a second language, you think ‘that sounds good’, and you then use it in your own work without thinking. This can be an issue because it’s usually standard for journals to run papers they receive through plagiarism checking software before sending them out for review. After all, nothing is more frustrating than working for months on a paper and then receiving an almost immediate rejection from your target journal.

Make sure you don’t get caught in the plagiarism trap!

It’s very important to be clear: what is plagiarism? A lot of people just don’t know, so here are some definitions

Plagiarism simply means ‘the appropriation of another person’s ideas, processes, results, or words without giving appropriate credit’. In academic writing, this means ‘citation’. If you’re unsure, be sure to cite. Appropriation means using or taking something that is not yours; thus, plagiarism is using another person’s words or ideas, considered academically dishonest because students, scholars, and faculty members are expected to do their own work. Plagiarism is therefore an issue in the academic environment and beyond; the use of information without crediting a source can harm your credibility as a researcher. Quite apart from the fact that if a journal identifies plagiarized text in your submission they are likely to reject outright and, maybe, add your name to a ‘blacklist’ of authors, preventing further submission to that outlet.

The rule of thumb here is that it’s important to cite if you make use of the works of others to gather information, make use of the works of others to support your argument, or examine the works of others to shape an argument.

Seems clear enough? Why then is there so much confusion about this issue?

Lets consider a few specific examples of commonly encountered forms of plagiarism:

(1) You are a member of the audience where research results are presented. You then use ideas described by one of the speakers in the design of your next research project. Citing material presented at conferences is often difficult, but this is nevertheless a form of plagiarism. The best thing to do here is to get in touch with the speaker and ask them if their idea has been published or if they were presenting for the first time at the meeting. It’s always possible to include a so-called ‘personal communication’ citation in your article if you want to refer to the idea.

(2) You are reading a journal article, chapter, or book. You paraphrase passages of text from the material you have been reading in the literature review of a manuscript you are writing. You must cite. This is an easy one to watch out for and avoid.

(3) You are reviewing a submitted manuscript. You decide to use novel research methods described in that manuscript to enhance your own research. This is a total no-no. One of your responsibilities as a peer reviewer is to maintain confidentiality; under no circumstances should you ever use material you see during this process in your own work. You must wait for the paper to be published and then you can cite it in the normal way.

(4) You are doing research using the Internet. You choose to use ideas from a website in the design of your next research project, and also use some quotes from the website in your literature review. You just have to cite the source in this case: commonly, people write both the URL and the date on which it was accessed when citing online materials in their papers. Many journals discourage this, however, preferring the use (and citation) of peer reviewed materials. It’s possible to do this, but check the author guidelines of your target journal or, if in doubt, ask the editor.

(5) You are writing a paper in English, and your native language is Chinese. When writing a review of literature, you use another author’s exact words because you are not confident about paraphrasing or synthesizing the ideas into your own words in English. This is form of plagiarism is very common but can be easily avoided by citation.

Finally,

(6) You are writing a manuscript for publication that is based upon your own previous research. You decide to include some exact text from one of your earlier manuscripts in the new paper. This is called self-plagiarism, a topic we’ve covered in more detail before; it’s possible to steal from yourself but, again, this is easily mitigated by citation.

Many people find the last of these ‘kinds’ of plagiarism the hardest to understand: how is it even possible to ‘steal’ from yourself? Surely, if you have written a paper and got it published you can then re-use the text and images as many times as you like. Not so.

People very often ask about this issue: ‘I wrote a paper in 2018; surely, I can use text or figures from that work in my own later work. What’s the problem? I wrote the first article, after all.’ The situation is not so simple, however, and academic publishing’s ethical policies in fact demand that anything we take from any other paper, even our own, must be correctly sourced and cited. Everything. So, even if I wrote a paper about academic ethics in 2018, if I re-use text in a later article in 2019, I have to cite myself: ‘as noted by Dyke (2018), the issue of research ethics looms large over the publishing industry’.

In particular, it’s critical to be aware of self-plagiarism so you don’t get caught out by it. I recall an incident in my own field from a few years ago; people started to notice that some text and figures in the papers of one of our colleagues were strikingly similar. Indeed, after a little digging by one journal’s editorial office, it turned out that this person had been recycling text in the Introduction and Methods sections of papers word-for-word (whole paragraphs in some cases) as well as reproducing the same figures over and over again without self-citation (in most cases you simply need to write, for instance, ‘this figure reproduced from Dyke (2018)’ in the caption). Self-plagiarism in this case turned out to be a serious issue for the colleague; he had to issue corrections to some of his previously published work and, worse, people heard about it, leading to reputational damage. Nobody wants to be known as someone who cuts corners in their publications.

On top of all this, there is also a potential copyright issue related to self-plagiarism. Bear in mind that in many cases, when you write a paper and send it to a journal, you are also turning over the copyright of your work to that outlet. Although not always, this is very often the case (this will be part of either the online submission system itself or a transfer form you will complete once a paper has been accepted). This means that in some instances if you want to re-use a figure from a previous paper of which you are the author, you might need to ask permission from the journal in question: ‘this figure reproduced, with permission, from Dyke (2018)’.

Research ethics, especially plagiarism, can be complex. It’s better to be safe than sorry, so if in doubt: check and cite.

Want to learn more? Research and publishing ethics ….

This section is sponsored by Virtus Publishing: You can get 20% off self-publishing your book with Virtus ….

In a series of posts within posts, our friends at Virtus Publishing will provide tips and advice covering many aspects of publishing. This next series will be an ongoing selection of language tips, covering areas that many copy editors (and authors) find difficult. These will be short and to the point.

Virtus Publishing Language Tip #11: “Who” versus “Whom”

Well-known example: For Whom the Bell Tolls. (See below.)

An error I see crop up very often in many places (including books, newspapers and magazines) is the misuse of “whom” when “who” is actually correct. More often though I hear it come up in conversation, usually from people who are unsure or unaware that there are actual rules and are simply trying to “sound smart.”

There’s an easy way to determine which is correct, provided by one of my favorite sources, Grammarbook.com.

Let’s take a look at their explanation. I’ve reformatted for clarity. As always, the end of the quoted material is denoted by the box (∎):

Rule. Use this he/him method to decide whether who or whom is correct:

he = who

him = whom

Examples:

Who/Whom wrote the letter?

He wrote the letter. Therefore, who is correct.

Who/Whom should I vote for?

Should I vote for him? Therefore, whom is correct.

We all know who/whom pulled that prank.

This sentence contains two clauses: we all know and who/whom pulled that prank. We are interested in the second clause because it contains the who/whom. He pulled that prank. Therefore, who is correct.

We wondered who/whom the book was about.

This sentence contains two clauses: we wondered and who/whom the book was about. Again, we are interested in the second clause because it contains the who/whom. The book was about him. Therefore, whom is correct.

∎

Let’s pause here: Grammarbook.com raises a very important issue I was referring to when I said that some people use “whom” in an effort to sound smart. Again from Grammarbook.com:

Note: This rule is compromised by an odd infatuation people have with whom—and not for good reasons. At its worst, the use of whom becomes a form of one-upmanship some employ to appear sophisticated. The following is an example of the pseudo-sophisticated whom.

Incorrect: a woman whom I think is a genius

In this case whom is not the object of I think. Put I think at the end and the mistake becomes obvious: a woman whom is a genius, I think.

Correct: a woman who I think is a genius

∎

So remember, the basic rule is simple:

If you can replace the word “who” or “whom” with “he”' or “'she,” use “who.”

If you can replace the word “who” or “whom” with “him” or “her,” use “whom.”

So referring to the picture at the top, who does the bell toll for? It tolls for her, so whom is correct.

It is very important to understand the distinction between the two examples. Keep this simple rule in mind when making any changes related to these words.

Like this post? Follow Virtus Publishing on LinkedIn!

Have you ever wanted to publish a book? Virtus Publishing’s self-publishing services can make it happen! A global service provider, Virtus has the industry experience and dedicated staff to turn your book idea into reality.

Send an email to david@virtuspublishing.com to set up a free consultation. Mention the keyword “Bell” and receive 20% off your first order.

I liked that in this post the Virtus language tip came afterwards. I prefer to first read Gareth's topic and later on the language tip. I hope this feedback is helpful.