Effective English Writing for Researchers (and Understanding Copyediting) ...

Have you ever wanted to publish a book? Virtus Publishing’s self-publishing services can make it happen! Read on to learn more ....

How can you write in English more effectively and easily?

The goal of this blog is to help you write effectively in English. I know, it’s not easy! Especially if English is your second, third, or fourth language. I’ll try to help.

Over the course of a series of posts, we’ll consider cognition, how to write effectively, and how to increase the resultant visibility of your research. We’ll cover some rules and guidelines as well as tips and tricks.

Writing effectively in English is all about learning to be an effective communicator. It’s not about grammar, it’s not about learning all the rules. Writing is a skill you can develop, not a talent. This is important to keep in mind as we get started …..

This section is sponsored by Virtus Publishing: You can get 20% off self-publishing your book with Virtus ….

In a series of posts within posts, our friends at Virtus Publishing will provide tips and advice covering many aspects of publishing. The first installment is a copyediting overview in three parts.

Copyediting Overview—Part 1: The Basics

“I asked the Zebra, are you black with white stripes? Or white with black stripes? And the zebra asked me, ‘Are you good with bad habits? Or are you bad with good habits?’ ...”

—Shel Silverstein, American poet and songwriter, 1930-1999.

To use the term “basics” in relation to “copyediting” understates both the role and the function of a copy editor. Although the production process within all publishing spaces has been shortened and tightened considerably over the past 30 years in terms of the time spent at any given stage, the role of the copy editor has grown more complex. The confusion among those not involved in this activity has increased as well. It can be just as confusing as the question above concerning the zebra.

The areas of confusion can be summarized by two questions:

· What does it include?

· What doesn’t it include?

Throughout this series we’ll be referring to a “manuscript” to mean whatever text the copy editor is editing: In our world these are usually either journal articles or book chapters. We’ll also be referring to the final “product,” rather than published journals or books. The concepts described are identical in all of these cases.

In today’s world the final product can include everything from printed matter, to something intended for consumption online (such as a website), or text to be read on a portable device, such as a phone or tablet. All of this material requires copyediting and the concepts are the same regardless of the type of final product.

Let’s start with a pair of simple definitions provided by The Chicago Manual of Style, edited for content. (Throughout, the end of quoted material is marked by this ∎.)

From the Chicago Manual of Style, section 2.2:

Manuscript editing. The manuscript editor makes changes to the manuscript (and, where necessary, queries the author) and demarcates or checks the order and structure of the elements (e.g., illustrations, headings, text extracts). ∎

From the Chicago Manual of Style, section 2.45:

Manuscript editing, also called copyediting or line editing, requires attention to every word and mark of punctuation in a manuscript, a thorough knowledge of the style to be followed, and the ability to make quick, logical, and defensible decisions. It is undertaken by the publisher when a manuscript has been accepted for publication. It may include both mechanical editing and substantive editing. It is distinct from developmental editing which more directly shapes the content of a work, the way material should be presented, the need for more or less documentation and how it should be handled, and so on. Since editing of this kind may involve total rewriting or reorganization of a work, it should be done—if needed—before manuscript editing begins. ∎

CMOS says the copy editor “makes changes to the manuscript.” What do these typically include? What is to be ignored? This is determined largely by the CE level, to be discussed in Part 2 of this series.

CMOS also says that CE is “undertaken by the publisher when a manuscript has been accepted for publication.” This is a critical point because the care with which the copyediting is done and the expertise of the copy editor sets the stage for all stages that follow: It can “make or break” a successful final product. This is the primary reason for ensuring that all copy editors are qualified: The work they do affects everything that follows until the product is released.

An important point to understand is that a copy editor need not be a “subject-matter expert” (SME) in the discipline or area discussed in a manuscript to successfully and effectively perform the copyediting. This has become a controversial issue: Many publishers disregard the fact that the copy editor’s concern is the language and the way in which the matter is presented, rather than the content itself. An author may discuss the inner workings of building a nuclear submarine in a manuscript: The copy editor does not need to understand anything about nuclear submarines to copyedit that text. In reality, an SME can be less effective as a copy editor because they will invariably be too interested in the content to notice the flaws in the presentation.

Many years ago there was a copy editor we’ll call Ryan. He held a Ph.D. in physics and was hired as a freelancer to work on higher ed physics books for a large publisher.

The authors hated him.

The managing editor was tasked with determining why. By reviewing his work the ME determined that Ryan was focused on the scientific correctness of the content: He went as far as to rewrite equations and formulas and include queries to the authors with these “corrections.” The problem was he was regularly missing all the elements he should have been addressing: misspellings, incorrect grammar, inconsistent punctuation, and various style issues.

The ME rang him up and advised Ryan that he was being moved to biology books.

“Oh! I don’t know anything about biology,” said Ryan, who was quite disturbed.

“Perfect,” said the ME.

Ryan went on to become a valuable resource as an excellent biology copy editor.

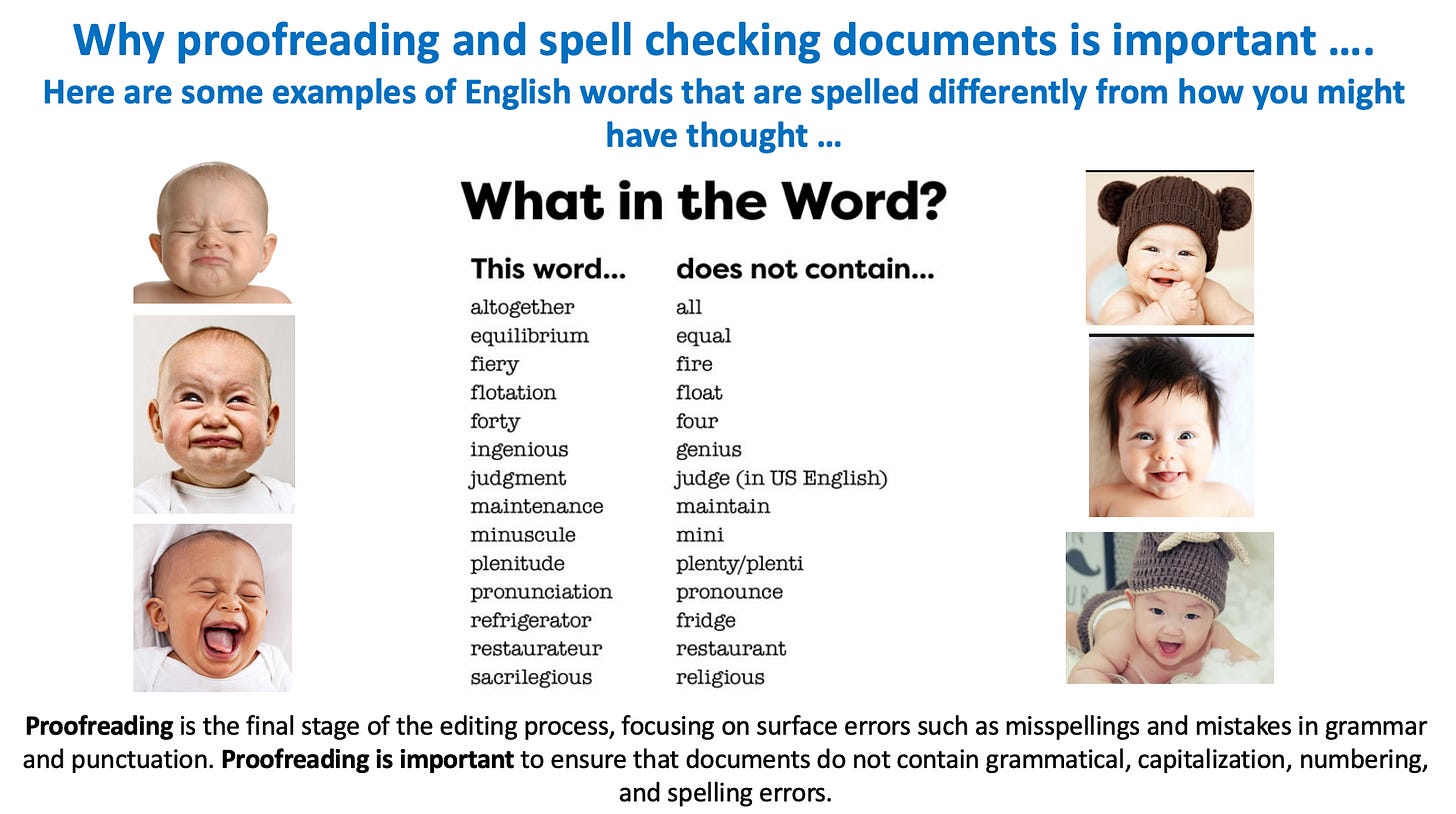

Experienced copy editors tend to spot errors in text everywhere (and sometimes don’t even see anything else!). How would you copyedit this sign? This would be an example of a Level 3 copyedit, to be discussed in Part 2 of this series.

Like this ‘post within a post’? Follow Virtus Publishing on LinkedIn!

Send an email to david@virtuspublishing.com to set up a free consultation. Mention the keyword “copyedit” and receive 20% off your first order.

Understanding your reader

We don’t write academic papers so we can pin them to the wall, or give them to our mothers as presents. No. We write academic research articles so others will read them and, hopefully, cite them. This is our goal: Writing a paper that does not get read and cited is almost as bad as not writing a paper at all. Readers are key!

We must appeal to our readers as academic writers. We must engage and capture their interest and do the best we can to make sure readers get to the end of our work and think: I agree! I do think that this is the correct, expected outcome. More on this later.

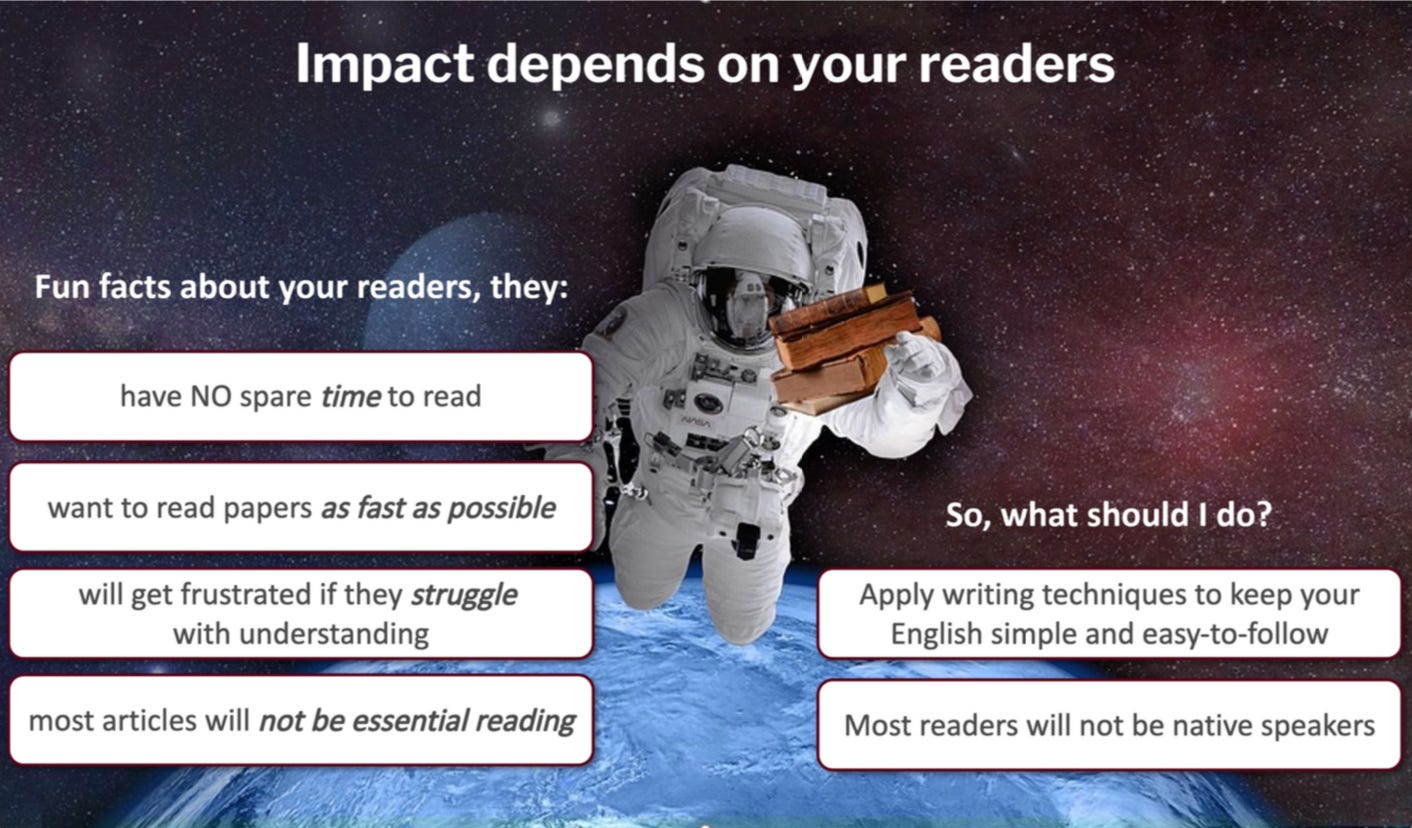

Here are some fun facts about your readers who, by the way, are almost certainly not going to be native English speakers. Where is most of the research in the world getting done these days? Much of it is taking place in Asia, in countries like Japan and China where English is not spoken as a first language.

It’s also informative to think about why we choose to share our research. What’s the purpose of an academic paper? Why write at all? The goal of writing a research article is to explain new information to readers in order that they will remember and use that content. You need to get your message across. So, your goals as a writer are to explain new information in such a way that readers will remember, retain, and use your new knowledge.

Cognitive learning: The basis for effective communication

Effective writers are able to understand their readers by applying three important learning principles. We’ll deal with each of these in turn: cognitive load theory, cognitive bias, and reader expectations. The first, cognitive load theory, has to do with understanding just how much new information your readers are able to process, while the second, cognitive bias, warns us not to assume that our readers know as much as we do (we’ll come back to this).

Finally, the logical presentation of information for readers is important: the readers of academic papers expect to see and absorb information in a certain specific order. This is the logical structure of an academic article.

Cognitive load theory: How much information can our readers process?

Did you know that research has shown that the human brain can only process between seven and nine new pieces of information at any time? This is cognitive load.

This feeds into our understanding of sentence structure and length. It’s best therefore to write using sentences that are shorter rather than longer: sentences 10 words in length tend to be recalled by readers 98% of the time, while those that are 20 words in length are recalled 85% of the time. The drop-off after that is significant: sentences 30 words in length are recalled 70% of the time, while those 50 words in length have just 58% recall.

What does this mean? We recommend that you aim for 10-20 words per sentence on average. Some longer and some shorter are still fine of course, but as a general rule: shorter sentences are better than longer cumbersome ones.

At the same time, aim for just one idea per sentence. This is the concept of topic sentences (which we’ll return to a little later on in this guide). Use semi-colons in sentences only when necessary and make sure you clearly and throughly explain your ideas to your readers.

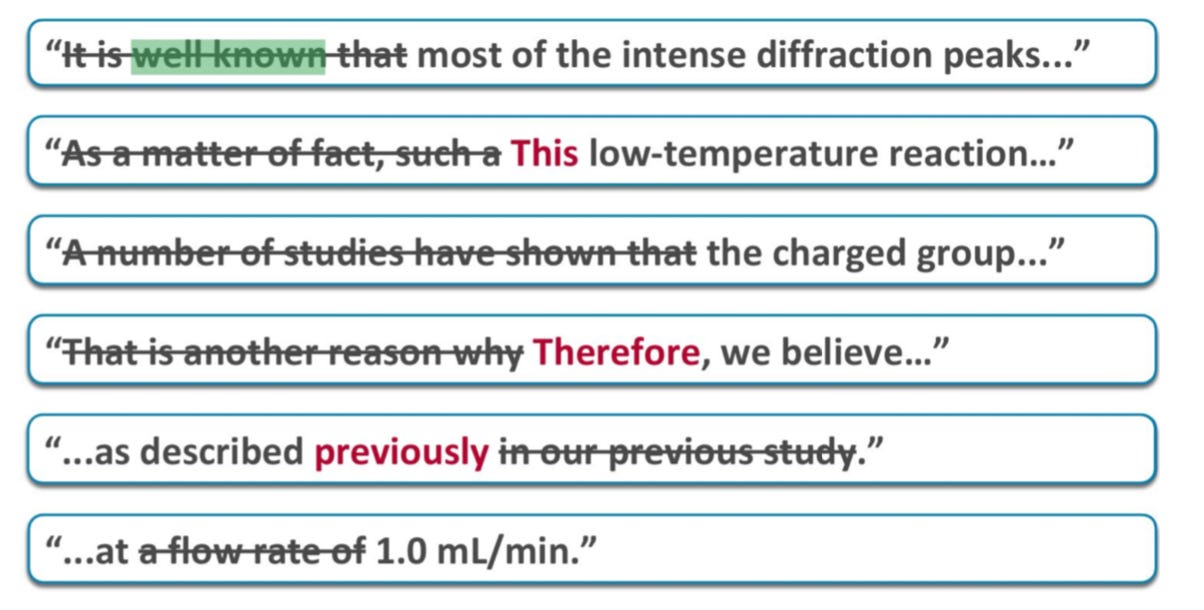

Cognitive load theory, the amount of information readers are able to process, also teaches us to avoid the use of unnecessary words that do not add value to ideas. Here’s a simple rule to follow in your writing: can you delete a word without changing the meaning of a sentence? If yes, then delete those words.

The best way to manage this is to read out your work aloud: read to your pets, read to your dog, read to your cat, read to your goldfish! Reading your work aloud helps to identify those cumbersome phrases and words that are not needed for meaning, words that do not add values to a presented idea.